| |

|

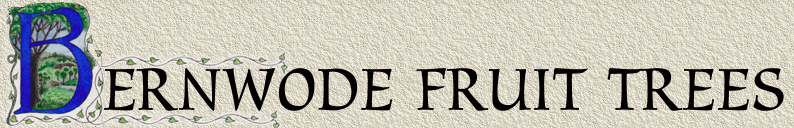

The

map below is probably the earliest known, that shows Wotton and

the surrounds in fairly accurate representation. The map extends

beyond the area shown here and bears the legend 'Sir John Godwin's'.

At the bottom right the wooded area is called Qwenes Wod and Quens

Wod and this surely means it was first drawn in the reign of a Queen.

The area was the King's Wood from the time of the Norman Conquest

and, apart from the revelation of this map, it has been known as

Kingswood since. Later additions have been made at some reprinting

as 'Grove Wood' and 'Morrels Pond' etc. are in a later script style.

The map is too early for Queen Anne and that would suggest that

the map was drawn in the time of Elizabeth I, perhaps even Mary,

before her. Sir John Godwin, of nearby Winchenden, lived from 1520-1597,

taking in both reigns. The black spot is the entrance to our nursery! |

| |

|

| |

It

might seem like ‘divine providence’ that, probably,

the most interesting and important orchard that has ever compelled

our attention is only ½ mile from the entrance to our nursery.

In

the early 1990s, two friends were out walking in the grounds of

Wotton House, Buckinghamshire, and came across a derelict orchard.

They brought us a variety of apples and pears and we visited this

orchard in haste. We knew little of the important Wotton Estate

at that time, but this orchard was quite obviously ancient and the

historical research followed. No histories mention this orchard,

though it appears on some early maps.

Now,

the thrill of every old orchard is incomplete without a context

and it is there that we must begin.

The

House and Gardens

Wotton

Underwood is recorded in Domesday and there has been a Manor House

there since the twelfth century, and in the hands of the Grenville

family, until the modern age. They later inherited Stowe and the

grounds of both were remade in the 18th century Landscape Movement,

in tandem, to some extent. The village, that was inconveniently

situated, was swept away along with the mediaeval Manor House, though

the Church and some dwellings outside the area of the garden plans

still remain.

The

historical papers of Wotton and nearby villages were bought by the

Henry Huntingdon Library in America as a job lot and many remain

uncatalogued, but some useful information has made its way out.

We can hope for more.

The

Grade 1 listed Wotton House was built between 1704-1714, some say

1717. This second house burnt down in 1820 and was rebuilt a few

years later in a more formal style.

Lord

Richard Grenville, as the 17th century gave way to the 18th, had

already started designs for a fully landscaped garden in the latest

style of the grand landscaping movement. The work was taken over

by London and Wise early on. London was the founder of the famed

Brompton Road Nursery in 1681. Wise became an apprentice there in

the early 1700s. Between them, they were responsible for many famous

garden designs including Blenheim Palace. London died in 1714 and

Wise went on to become Gardener to Queen Anne and George I, designing

and replanting several royal palaces and other gardens. He died

in 1738. Interestingly, they were also the authors of ‘The

Retir’d Gardener’, an influential work that contained

lists of fruit varieties, first published in 1706 and again in 1717.

Though there is no evidence to suggest they included fruit trees

in their landscaping at Wotton, it was a remote possibility, but

one which will seem very remote as our narrative unwinds.

Up

to the middle of the century, the young Lancelot (Capability) Brown

(1716-1783) took over much of the work and added to the designs.

It is believed he went to Wotton before he went to Stowe and Wotton

might have been his first Landscape Garden. It is also thought that

after his work at Stowe Landscape Gardens, after the ownership of

Stowe came to Lord Grenville by marriage, Brown returned to work

further at Wotton. William Pitt the Elder married into the family

and was also said to have helped with the design, sometime in the

early to mid-1700s. It has been suggested by some that grounds development

started in the 1750s but London and Wise were dead by then and this

view is surely wrong. However, we must not get sidetracked into

the fascinating subject of the Landscape Movement and Capability

Brown. The orchard is our focus. The transformation of the grounds

at Wotton was thought by most to be complete by the middle of the

18th century.

|

| |

The

Village

As with most medieval

manors, tenanted properties, both domestic and farm holdings,

littered the area. A map of 1657 shows great detail of the village

at Wotton. This and other maps in the Buckinghamshire County Archives

have been very useful in piecing together the history of this

very old orchard. We are very much interested in what existed

before the village was removed, as will become clear. Since this

orchard was preserved and safe from the plans of London and Wise

and Capability Brown, it might seem 17th century and would appear

to predate the removal of the village. It would make this orchard

the only surviving part of the pre-landscape age of the Wotton

Estate and the oldest part of the current Grade 1 listed House

and Gardens.

This map was dated,

with some uncertainty, at 1657, but it might have been drawn earlier.

It does look, from our experience, of the style of late 16th century

similar maps, as if it was earlier. Another map, dated 1649, might

conversely have been later than this date. The important question

is ‘when was the village removed to make way for the grand

landscaping’? Within the garden plans the entire village,

buildings and all the tenants were removed. Even to the south

of the landscaping the land was cleared and is now within Lawn

Farm (once owned by the Grenvilles) – clear pastures. Some

parts would certainly have been gone just before building of the

new house started in 1704. It rather looks as if it was all cleared

earlier, as Lord Grenville’s garden plans took shape in

his head. There has been a belief in some quarters that the village

was cleared following the Wotton Enclosure Act, variously put

at 1735 and 1743. This was the first or second Private Act for

enclosure in the country. However, the villagers and their holdings

must have been gone by this time as the garden landscaping was

near complete.

The original mediaeval

Manor House is shown on this map of 1657, marked as Grenville’s

Yardes, Barne and House and a short distance to the south and

east of the planned New House. The map has been overmarked by

the garden designers with lines of tree plantings and also shows

the location of the New House. Historic England and all other

histories that we have found say that the location of the original

Manor House is unknown, but this map shows it clearly. There is

an adjacent kitchen garden and two adjacent orchards marked. The

small ‘Old Orchard’ we are considering here was not

needed by the mediaeval manor house and was quite distant. When

the new house was built and Grenville’s kitchen garden and

orchards were eradicated, the ‘old orchard’ would

have been a long walk away for a house maid, having to walk around

the ‘New River’ which had been inserted across the

path between the new House and the ‘old orchard’.

A quarter of a mile or more! Besides which, the new House created

its own orchard and kitchen garden adjacent to the House. This

orchard became part of Lodge Farm and the orchard still existed

until the end of the 1990s. We grafted the trees there and have

them with us. This orchard then gave way to a swimming pool and

tennis court, now in the ownership of Tony and Cherie Blair.

The mediaeval house

and the New House had no interest in the ‘old orchard’.

So whose orchard was it? When was it in existence and why is it

still there?

1657 map

|

|

|

1657 map

The

Old Orchard

On

this 1657(?) map we see the house/garden and wider holding of Thomas

Lovell. It was one of the largest holdings on the map and he must

have been a man of some significance. Note also the ‘The High

Way’ that dips and sweeps past his holding. The top part of

his holding is precisely where the ‘old orchard’ exists

today and the line of The High Way was adopted by the garden designers

as the path that would be followed for the ‘walk’ they

created at the south of the redesigned gardens. Past Thomas Lovell’s

holding, the path would cut south-east and head towards the enlarged

lake, alongside the new avenue of trees. The deviation of The High

Way around Thomas Lovell’s holding was retained.

|

| |

1657 map |

|

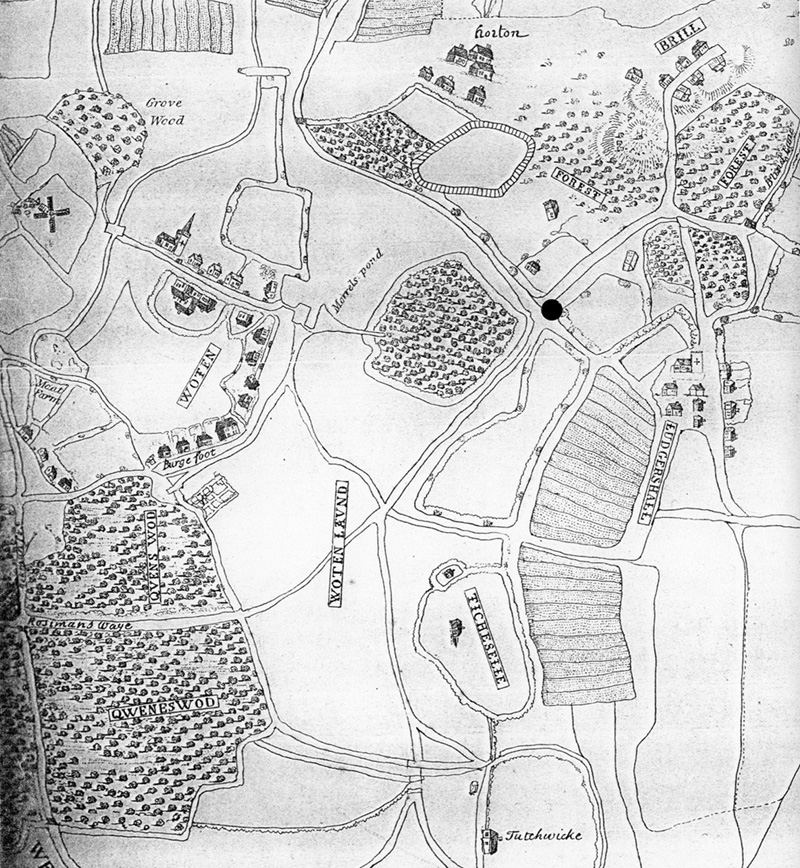

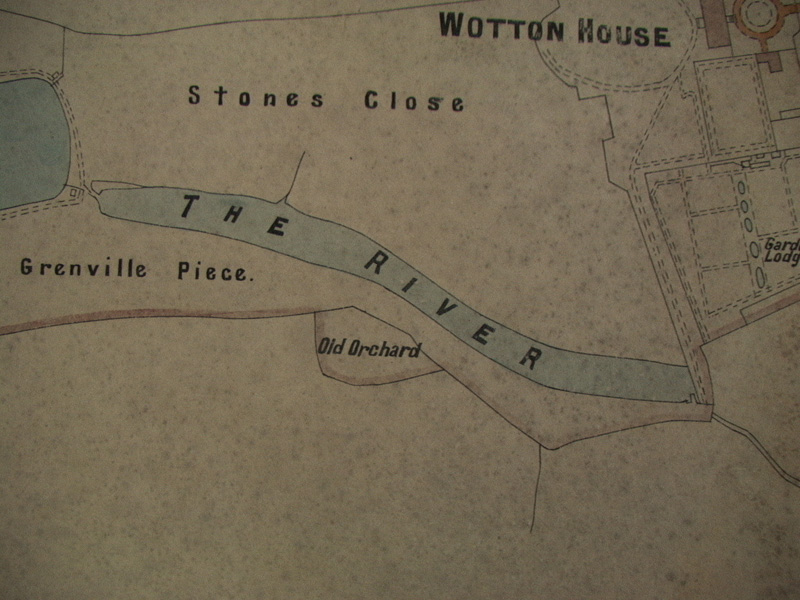

We

now look at the 1649 map which seems to be a bit anachronistic,

as it shows far fewer dwellings and holdings than the 1657 map,

as if the 1649 map was later and the 1657 map earlier. Perhaps it

was an earlier map but solely concerned with recording the Closes

and ignoring dwellings and holdings. As with the 1657 map, this

1649 map has been overmarked by the garden designers. There are

three significant features here.

1.

It shows a yellow/orange line added by the garden designers to mark

the path of the Walk on the edge of the reconstructed gardens, following

The High Way, in a detour loop, north of the dwelling marked there,

before heading south east again.

2.

This dwelling is that of Thomas Lovell, as it appears in very much

the same shape and location as the 1657 map, but without the wider

holding he had in the 1657 map. The line of the walk has somewhat

truncated part of Thomas Lovell’s holding, but part remains.

This is ‘the Old Orchard’. If this 1649 map was later

and Thomas Lovell was still living, perhaps he was a valued retainer

for the estate and his dwelling continued to exist post-garden redesign.

His house is outside the redesign, as was ‘The Old Orchard.’

The dwelling has gone and is now part of the clear fields of Lawn

Farm.

3.

The marking of ‘The New River’ might be outside the

awareness of the garden historians of the ages, since it was considered

to have been made in the early to mid 1700s, when the gardens were

redesigned. Yet here it is, marked in the old style of lettering,

on a map dated 1649! Could it be the gardens redesigning commenced

much earlier than has been supposed and if the dates of the maps

of 1657 and 1649 are correct, why was it not shown on the 1657 map?

Surely the 1649 map is later than the 1657 one. Interestingly, the

New River also deviated its path to make allowance for the route

of The High Way and Lovell’s property.

1649 map

|

1649 map |

|

| What

Happened Here?

Thomas

Lovell had a small house and yard. He also had an orchard north

of his dwelling, within his larger holding. The various garden designers

used the old ‘High Way’ as the limit of their redesigns

and for the ‘Walk’, which went around and north of Lovell’s

orchard. They trimmed a bit off the northern part of his holding,

but certainly deviated their Walk around the main part of it. They

had no reason to remove the orchard. It was outside of their plans

and probably provided some welcome mature trees to the view, at

a time when most else in the view were mere saplings. Perhaps, being

fruit tree nurserymen, London and Wise could not bear to destroy

an orchard. The orchard had no value for fruit as other new orchards

had already been planted next to the New House. No-one had any interest

in replanting it, or even using it, since now there were no dwellings

for some considerable distance. It was left alone.

A 1798

map (when all landscaping was complete) shows the line of the boundary

of the landscaping and shows the ‘bulge’ around Lovell’s

orchard, but only marks trees sparsely, where they are not part

of the tree avenues.

1798 map |

|

|

|

|

| The

map of 1847 shows the redesign complete and the orchard there beyond

the boundary. It is marked 271, which looks to be a denomination

used in the enclosure award a century earlier. Enclosure awards

were often numbered such and this later map might have found value

in using the same key to parcels of land. This orchard is still

part of the Wotton Estate, while, to the south, all is now part

of Lawn Farm.

map1847

|

|

1847 map

|

|

The map of circa 1890,

has now finally acknowledged that there is an ‘Old Orchard’

there and this is much the same size and shape as exists today.

about 1890 map

What

happened to Wotton in modern times?

In

the first half of the 20th century, death duties left the estate

to neglect. In the middle of the century, the estate was sold to

a charity and it later became a boys’ boarding school. Parcels

of land were sold to local farms. The House was derelict by 1957

and Buckinghamshire County Council, who then owned the estate, had

decreed its demolition. Elaine Brunner discovered it and bought

it with the grounds for just £6000, and just two weeks before

demolition was due. She started the restoration, albeit slowly,

given the scale of the task and restrictions on finance. She also

bought back 400 acres of land once part of the estate.

At

her death, in 1988, her daughter April Brunner and her husband David

Gladstone, descendent of the Victorian Prime Minister William Ewart

Gladstone, took over the task. April is no longer with us and David

is planning the succession.

Estate

Manager, Michael Harrison, oversaw much of the gradual restoration

and took great interest in the history and the enormous amount of

work in maintaining the grounds and restoring the features. It was

in the early 1990s that we first met him, and shortly afterwards

David and April Gladstone. We thank them for their help and support

in our own research into the ‘old orchard’ which is

the focus of this account.

|

|

The

Orchard in Modern Times

When we first saw this

orchard it was heavily overgrown and Michael Harrison confirmed

that nothing had been done with it for decades. It had a close

encounter with extinction when Elaine Brunner asked Michael to

clear it. He wisely found more pressing work!

Trees had fallen, roots

had suckered and grown tall and thick, brambles had become widespread

and the shade canopy made proper knowledge of the fruit difficult

at the start. Michael Harrison brought some sanity back, over

time, with extensive clearing of unwanted bramble and rootstock

growth and only judicious pruning. We grafted all the trees at

the outset, to preserve them here and for the future. We passed

back to Michael a new tree of each in the orchard and he planted

them in the spaces of the orchard, for long term continuation.

The orchard is about

½ acre, roughly the shape of a long ellipse, and the uneven

ground is crossed with a depressed channel, probably an ancient

walkway. There are traces of other paths, marking the passage

of relentless feet and the toil of barrows and carts, over countless

years. The landscapers of the gardens were meticulous in their

imposition of flat grounds everywhere, but this did not happen

in the orchard. Another reason to believe it was never part of

the plan. The orchard ground is very uneven.

To the north are the

Gardens and House. To the south is open farmland – now separately

owned and divorced from Wotton Estate. The orchard is ¼

to ½ a mile away from the house and there are no buildings

or gardens close to it for some considerable distance in other

directions. It is alone on the edge of the estate. It is hard

to see why anyone would take any interest in it or replant it.

The absence of any middle aged trees, that could not have come

from re-growth, rootstock growth or random seedlings, leads to

the view that the orchard was frozen in time. Another strong suggestion

for this is that there are significant spaces in the orchard,

where once there would have been fruit trees. Old trees die out,

but why were newer ones not planted to fill the gaps? Long term

lack of husbandry is the compelling conclusion.

The Endicott Pear in

Massachusetts was planted in 1630 and is still alive, with a full

and unbroken history of its existence. Why should we not believe

we might be seeing fruit trees at Wotton of excessive age, even

if not quite as old as 1630?

When first seen there

were 10 apple trees, 5 pears, 7 hazelnuts (of more than one variety),

and a single plum that turned out to be a Blackthorn tree of significant

age, all by itself. One of the pears and two of the hazels have

since died. One apple looks as if it might succumb soon. The gaps

in the orchard might have given space to another dozen or more

trees. This was a mixed domestic orchard from what we see now,

with eating and cooking fruits and space for cider and perry trees,

plus nuts for the winter. We might surmise that some of the missing

trees were cherry and plum, both of which tend not to live as

long as apples, pears and nuts. We have had all the apples and

pears DNA profiled and all except two have come back as unmatched

against any variety in the National Collection. The two that were

matched were a pear ‘Autumn Bergamot’ and an apple

‘Catshead’, both of which have origins by the 17th

century and probably in the 16th century. That so few of the trees

had matches and that there were no 18th or 19th century varieties

found there, speaks volumes.

The pears

could be some of the oldest growing in Britain, while the apples

are surely setting records for the potential age of apple trees.

All the trees fruit, so pollination is still covered within the

orchard. We see that at least some of the trees were grafted,

judging by rootstock growth, and that there were no repetitions

of varieties, possibly excluding the nuts. We do not see the works

of Man in this orchard between the laying out of the Gardens and

the 1990s.

The

Fruits

Pear 1

A small perry pear, ripe in September and very sweet and very

tannic, though the tannin is less if kept for a while and it can

then be pleasant to eat. It does not store for very long. A very

tall, large- trunked and very old tree. Now named 'Wotton Morsel'.

Apple

2

A mature tree possibly 100 years plus and upright. It does not

look as old as the rest. A mature younger shoot from the base

is the same as the rest, from blossom and fruit. Waxy, small,

pale green becoming yellow fruit, with a rare blush and few pale

streaks in the sun, with warm brown russet patches and nets. Fruit

is ripe in October and is fairly crisp, fairly sweet, with pleasant

acid, juicy and tannic. It is possibly a seedling or a sucker

from a tree now gone. It might also be the original variety, shooting

from a decayed trunk. It would probably make a useful single variety

cider apple. Now named 'Wotton Revival'.

Apple

3

A truly ancient tree which fell over many years ago and re-rooted

from the trunk. A new vertical shoot is now mature. The original

trunk when first seen had nearly disappeared into the ground.

Now, the signs of it have almost gone. Some fruit drops in October

but the main drop is in November. Medium to large rounded apples

with matt green skin with light red streaks in the shade but fully

red in the sun. An excellent, crisp, dessert apple, with a complex

flavour when young, becoming richer. At the end of November it

starts to soften but the flavour is good, sweet and juicy. It

will last well until the end of the year. Cooked, it keeps its

shape but would mash and is rich, and sweet, needing no added

sugar. It does not discolour when cut. One of the best in this

orchard and not dated because of antiquity. Michael Harrison has

named this Wotton Prolific as it always bears very well.

Apple

4

A very old tree, fallen over and rooted from the trunk. The vertical

growth is now mature. The old trunk had largely gone in the 1990s.

The fruit is unusual, being irregular, rather flat and very conical

and of variable size, some over 3 inches wide and 2-3 inches deep.

The flesh is sharp and hard, but rich, in October. In November

it is sweeter, still sharp and with a strong flavour. By December

it is perfect – still juicy, rich and sweet but still a

little too sharp to eat raw. Cooked, it keeps its shape well and

is powerfully rich, sweet, very tangy and needs just a little

sugar for perfection. Now named 'Wotton Enigma'.

Apple

5

A fallen tree that had rooted from the trunk. The rootstock had

suckered significantly. A medium sized, flattened, round apple

ripe in October to November. The skin is dull green, and russeted,

becoming amber with a warm blush and a few streaks. In October

it can be a little sharp, but it is also sweet with a good flavour.

It is best in early November when the flesh is tender and juicy.

It will last to December and though it tends to shrink and soften,

it remains sweet, rich and juicy. Now named 'Wotton Resurgent'.

Apple

6

This tree is tall and upright, with a modest girth, though the

trunk is very weathered. It is hard to say if it is a seedling,

a sucker or a new trunk grown from a fallen tree. It looks to

be 100 years or more. This is the latest flowering tree in the

orchard but others are still in flower for pollination. Apples

drop in mid-October and are still intact on the ground in mid-November

and into December. The apples are of variable shape, small and

sweet, without much acidity, a little tannic and a bit dry. They

start pale green and turn greenish yellow with an occasional amber

patch and a few streaks. It might be a useful Bittersweet cider

apple. It is a very prolific cropper and might reveal other qualities

if pruned or grown on a younger tree. Now named 'Wotton Autumn

Carpet'.

Apple

7 and 10

Two ancient trees that had fallen and re-rooted from the trunks,

with several upright re-grown trunks, now old. These two trees

had us (and Michael Harrison) fooled for years. The fruit was

so variable from year to year, and variable on each tree in the

same year, that we all assumed they were the same variety –

the apples of both being large, mainly green turning pale yellow,

heavily ribbed, and both of similar taste and excellence, either

for eating when fully ripe in early November or cooking. Both

trees cropped well, came into flower at the same time and with

seemingly the same blossom characteristics. They seemed to match

what we knew (then) about the long-lost Costards and we named

them ‘Wotton Costard’. (We now know a fair bit more

about Costards and please read our article on this website) We

took cuttings for grafting from Tree 7, as Tree 10 was then ailing

with little new wood. We later grafted Tree 10. This is now close

to death. When we had these Wotton trees DNA profiled we were

not surprised when Tree 7 came back as unmatched. We were surprised

that Tree 10 was Catshead. This now makes sense. It had always

seemed odd to us that such a mixed orchard would have two trees

of the same variety. Now we know why. Tree 7 is Wotton Costard

and Tree 10 is Catshead.

Apple

8

This is a large-trunked, tall and upright tree, first found with

a rash of large suckers at the base, from the rootstock, and bearing

different apples from Tree 8 – so it was clearly a grafted

tree. Whether the tree now seen re-grew from a fallen, broken

or decayed former trunk cannot be ascertained. The apples are

medium sized, roundish and lightly ribbed at the stalk and the

eye. Sometimes there is a little russet on the skin, but usually

the translucent skin is smooth, pale green and with amber red

and maroon streaks. In some years this tree has the habit of producing

ripe apples in mid September and further ripe apples over October.

When gathered they are crisp, juicy, tangy and sweet with a good

flavour, but they do not last long. After a few weeks they become

cidery in flavour and soft. We named this tree ‘Underwood

Pippin’.

Pear

9

This old pear is still upright, healthy and bearing well. It has

enough tannin to mark it out as a perry pear, and is sweet and

juicy too. The tannic flavour tends to fade a bit with storing,

though not enough to make this a good eating pear. Pears are small

and often irregular, becoming ripe in October and lasting a short

while. Though they stay juicy, the flesh becomes mealy. We have

named this tree ‘Duke of Buckingham’ after the long

association between Wotton and the Dukes of Buckingham.

Apple

11

This ancient tree is upright, but is heavily decayed in the trunk

and broken off at 8 feet. A new trunk is growing from the side

of the old trunk, where the limited living tissue is still in

touch with the roots. It is quite a unique apple! The very hard,

bright green fruit is quite inedible until the apples have over-wintered

on the tree and are then gathered in January or February, when

they are best stored for a while longer. The flesh before ripeness

is without sharpness or bitterness and only with a little sweetness.

Eventually, they become sweet, juicy enough and with a good flavour.

As they mature the glossy green skin becomes paler and with some

warm blushes in the sun. Unfortunately, we and Michael have not

been able to test enough apples for long enough, thanks to the

squirrels who make off with them and we do not yet know their

full virtues in cooking at the end of their storing time. In early

February, they keep their shape when cooked with a sweet lemony

flavour. This apple might just be the long lost ‘Deux Ans’

aka ‘John Apple’, known to Shakespeare, as it matches

no other apple, sufficiently described. We can, of course, never

be sure. Now named 'Wotton Endurance'.

Apple

12

The tree is upright, mature and old, but of uncertain age. The

apples are small and the blossom is very attractive. Ripe at the

end of August, into September, the flesh becomes softish a few

days after picking. The flesh is very fruity, juicy, sweet and

crisp straight from tree and would be very good for juicing. Now

named 'Wotton Nectar'.

Pear

13

An ancient pear that fell many years ago onto soft moist ground

and grew new roots from the trunk, flat on the ground. Much of

the old trunk remains, slowly rotting into the ground, while several

new trunks have grown vertically from the old one. Having small

and distinctly rounded, apple-shaped pears, suggested a very old

variety. We named it Capability Pear, for obvious reasons, many

years ago now. The pears are green with variable russet, ripening

to yellowish. In September the fruit is not quite ripe but can

be pleasant to eat, being juicy, sweetish, a little acid and with

a nutty flavour. The flesh is granular and sometimes a bit coarse,

but in October the flesh is softer, sweeter and richer. They do

not last long after that. This tree was DNA profiled by us and

was found to match ‘Autumn Bergamot’ in the National

Fruit Collection, a pear that is certainly 17th century, if not

earlier in origin. Given the matching descriptions for these two

pears, we have accepted Autumn Bergamot to be the correct name

for this pear.

Pear 14

A curious pear! The

tree was ancient and tall when first seen, in excess of 20ft.

The fruit is usually ripe in mid-October, green with russet at

the stalk and eye and sometimes having a mahogany cheek when in

the sun. The pears can be lumpy, irregular and waisted. The skin

is rather like an avocado. The stalk end sometimes produces a

fleshy lip. As the skin turns yellowish, the pears are ripe, but

over-ripe when fully yellow. They decay from the inside out when

fully yellow. The flesh is soft, coarse, granular and slightly

dry but is very sweet with a good flavour. This pear very much

belongs to a bygone age. Now named ‘Wotton Peculiar’.

Pear

15

When first seen, this

ancient tree was leaning and only supported by neighbouring trees

and ivy. The trunk was hollow and the only growth was high up

and sparse. We were able to graft new trees before this pear finally

died a year later. The pears are small to medium sized, a little

irregular and dull green, becoming yellow with a carmine blush

when ripe in late September. The flesh is juicy, sweet and a little

tannic. Now named ‘Wotton Reclaimed’.

Apple

17

This apple is of questionable age and merit. It

is mature and upright – perhaps 100 years old – but

not of the girth of the other old trees. Perhaps it was a seedling

that grew unobserved over the ages or a shoot from a rootstock

that grew to tree size, while its parent tree died and rotted

away. The leaves are small, glossy and rounded while the flowers

barely have any petals to speak of. The bark is different from

other apple trees. It is an odd tree to find there. The fruit

is small, green-yellow, crabby, sharp, tannic and only a little

sweet.

|

|

|

|