| |

|

|

|

| |

THE QUEST FOR THE COSTARD

Updated 2/11/22

|

If

the historical references are complete, then The Costard

(sometimes written Costarde in old references) is the second

oldest known English apple, second only to the Pearmain,

which was first recorded in 1204. The Old Pearmain and more

than one Winter Pearmain, still known, are probably not

the apple of 1204, but that is another story. The age of

the Costard makes it very special and it is unsurprising

that it has occupied many minds over the centuries. Today

it remains a compelling and vexing issue for the many who

hope to rediscover it. The quest has become something of

a mediaeval romance, where all the pleasures, adventures,

intrigues and diversions are in the ‘seeking’

and will probably never be in the ‘finding’.

The narrative is a long one, and open-ended. Such have been

the long breaks in its recorded history, such has been the

confusion between the Costard and the Catshead and so few

and inadequate have been the scant descriptions of the Costard,

that we barely know what we are looking for. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Where does the name

come from? Almost certainly it comes from the Latin word ‘Costa’,

meaning a rib, a flank or a side. Costa has become the stem

of many more words, such as Coast in England or Côte in

France, meaning a hillside. So we have our first clue. The Costard

is ribbed or sided. An alternative suggestion for the origin

of the name comes from various references in Tudor times and

later in Shakespeare plays, such as King Lear, Richard III and

Love’s Labour’s Lost, where ‘Costard’

was used in place of a ‘Head’ and even as the name

of a character, but there are no supporting usages of the word

by others, as a ‘head’, and it must simply have

been a favourite word of writers before, during and after Shakespeare's

time, perhaps signifying something large and hard – like

a Costard. The Oxford Dictionary gives one origin for Costard

as ‘applied derisively to the head (arch) 1530’.

Alternatively and though very speculative, the origin of the

word Costard might have been associated with the word 'Cust',

which the Oxford Dictionary tells us comes from the Old English

word 'cyst' meaning 'choice' or 'excellence'.

There is always the

possibility that the Costard was originally French. George Lindley,

in ‘A Guide To The Orchard and Fruit Garden’, 1831,

though wrongly considering that Costard and Catshead were the

same (more later) noted that there was a ‘Coustard of

the Normandy Gardens'. There was also an old apple called Côtard,

known in Jersey, as a cider apple. Some years ago now, we were

in touch with Brian Phillipps and Rosemary Betts, of the Jersey

Cider Orchards Trust, who told us of this apple in their collection

and its earlier history on Jersey. More recently we have exchanged

many emails with Vincent Obbard, Seigneur of Samares Manor on

Jersey, where Vincent and wife Gillie have a wonderful botanical

garden, including several traditional fruit varieties, including

the Côtard. Vincent sent apples to us and later scions,

which we grafted for new trees here. We had the dna tested and

it was matched with Bulmers' Norman. On reflection, the apples

did appear to be very similar to Bulmer's Norman! It is possible

this apple was on Jersey before Bulmers collected cider apples

in Normandy and renamed them, though the apple does not have

much in common with the Costard we seek. It might also be the

result of an error in grafting. Either way, there does not appear

to be a different Costard on Jersey, known now. There is another

ribbed green apple, without a name, that Vincent has sent us

and which has an umatched dna. We are still observing it.

Still considering

the 'French Connection', perhaps there was French knowledge

of an English apple. In 1597 Sir Thomas Tresham wrote a document

mentioning that an apple called ‘French Custard’

was growing in Mr Dean’s garden at Ely. However, there

is no known mention of a Costard in any of the reference works

in France, through the ages, though their records have been

more extensive and often much earlier than ours. Curiously,

the word Costard does exist in French, meaning a costume or

suit.

In England, the commonly reported

first reference was in 1292 when it was mentioned as Poma Costard

in the fruiterers’ bills of Edward the First. The fruiterer

to the King bought 300 pounds of Costards to supply the entourage

when Edward stayed at Berwick Castle, during his campaign in

Scotland. Taylor, in 1946, in ‘The Apples of England’,

gives a slightly later date of 1297 - when they were sold for

a shilling per hundred at Oxford. He adds that the price of

29 Costard apple trees was 3 shillings in 1325. Teresa McLean,

in her excellent book ‘Medieval English Gardens’,

1980, has reported some interesting observations from early

authors. She said “The most popular medieval apple was the Costard,

which made good cider and good eating” and “They

were good, vigorous growers, their bark yielding a red dye,

and they were the national favourite until the 17th century”.

McLean comments upon the Earl of Lincoln, who came into the

possession of a property at Holborn, subsequently known as Lincoln’s

Inn and Lincoln’s Inn Fields, in 1286. He was a keen gardener,

having many gardens, and made a substantial income out of selling

fruit and fruit trees. She noted that he obtained apple and

pear cuttings from the Continent and that “The Costard apple arrived in England at about this

time, as did the Pearmain, used for making cider, and they were

probably both among the new breeds of apple the Earl imported.

We know for certain that he got two cuttings of the Costard”

(reference unknown). If the Costard was new from the Continent

in 1286 (the earliest date suggested) then it is hard to see

how new trees, from two cuttings, would have been capable of

generating 300 pounds of apples for Edward’s troops and

household in 1292. The solution lies with a barely known phrase

used by Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln and also known

as Robert Greathead and Robert of Lincoln. He lived from 1175

to 1253 and spoke of 'apples and Costards'. Not only does that

place the Costard in the first, not second half of the 13th

century, possibly predating the Pearmain, but it rather implies

that the Costards were viewed as a class of fruit standing apart

from apples.

Moving forward in time, Rogers,

in the History of Agriculture and Prices (1886) has discovered

that "In the year 1345 some

fruit is called costard at Letherhead, and is sold at an exceptionally

high rate." In the 14th century, having been copied

in the 17th century, were several Anglo-Norman medicinal cures

for a wide range of ailments. One passage read

"Pur flux de ventre..tornes pur chaude meneysoun..pour

chaude meneysoun: pernez un poume costard" - For

something that runs of the belly... turn to chaude meneysoun

(the same as flux, something that runs): take a pomme costarde.

In short, for diarrhoea, dysentery or excessive menstruation,

eat a costard. The Costarde was mentioned in the ancient poem

‘The Pistel of Swete Susan’, thought to have been

written around 1390. It says "be costardes comeliche in cuppes pei cayre".

Comeliche = Comely, Cuppes = Cups and Cayre means gone or over.

We have seen it elsewhere that Chaucer (in the 14th century)

wrote "your chekes embolmed

like a mellow costard", though we do not have a

date. John Lydgate, and English monk and poet recorded before

1435 "The ffruytes which more

comvne be Quenynges, peches, costardes and wardouns"

- The fruits which more common be Queenings, Peaches, Costards

and Warden Pears. A reference from 1450 was noted in T.Austin's

'Two 15th Century Cookery Books' -

"Take Costardys, Perys, &

pare hem clene & pike out be core".Take Costards, Pears, peel them clean and decore them.

In 1519, a record from the Wardens' accounts of the 'Worshipful

Company Founders City of London' said "Gret costerd with peyores & wyn". - Great Costard with pears and wine.

This might suggest that if there was a Great Costard, there

was also a lesser one. In 1622, the poet Michael Drayton published

his 'Poly-Olbion' and included

"The Wilding, Costard and Pomwater" as he wrote of apples in Song18, p298. In 1655, T. Moffett and

C.Bennett, in Healths Improvement.... said “Some (apples) consist more

of aire then water,… others more of water then wind, as

your Costards and Pomewaters, called Hydrotica.” We then encounter various references to Costards as 'heads'

in a derogatory way. About 1515, the play Hyckescorner, by De

Worde includes

"I wyll rappe you on the costarde with my horne". In 1556 the Udall play 'Ralph Roister Doister' says "I knocke your costarde if ye

offfer to strike me".

In 1606 Shakespeare's

King Lear and also other plays by him used the word as an alternative

to 'head'. In 1723 Williams, in 'Richmond Wells' also used the

idiom as did Walter Scott in 'Rob Roy' in 1817. Perversely,

when the apple was no longer known, the use of the word as a

'head' continued, as in 1880, in Webb's translation of Goethe's

'Faust' and in 1928 in Bennett's 'Vanguard'.

Returning to Costards as apples,

a very interesting episode and exchange, between the widow of

Sir Thomas Tresham (1543-1605) of Lyveden New Bield in Northamptonshire

and Robert Cecil at Hatfield House, Hertfordshire, took place

at the start of the 17th century. The Greatt Green Custarde

was part of the narrative and will be returned to at the end

of this appraisal of the Costard. Dame Muriel Tresham donated

fruit trees to Hatfield House in 1609, probably as a 'Thank

You' to Robert Cecil for calling off her persecutors. Sir Thomas

had been a Roman Catholic and stood on the wrong side of the

times, often perilously. After his death, his widow was still

facing antipathy. In 1609 she complained of her treatment to

Cecil and offered him 50 trees 'out

of Lyveden orchard towarde the planting of the orchard which

I heare your Lordship intendeth at Hatfeyld'. A

receipt for the trees exists at Hatfield though there is no

record of whether the trees were bought or were a gift. We thank

Kate Harwood for this account and on several other matters.

Her passion and knowledge are peerless. The narrative carries

on. Kate adds another

reference - Andrew Eburne, Garden History, Vol 36 No 1 Spring

2008 page 129. Dame Muriel said 'I

think no one place can furnish your Lordship with more and better

trees, and of a fitter growth, than this ground. For my late

worthy husband, as he did take great delight, so did he come

to great experience and judgement therein' and 'I will have Catshead,

and Dr. Harveys, and French Crab for making cider … And

Great Green Costard and Winter Queening … though middling,

it will keep til Lent - As to Pears, I must have Black Worcester.

Aye. ‘tis a very excellent good pear that will last the

winter'.

|

Another interesting

connection was between Robert Cecil at Hatfield and John Tradescant

the Elder (1570-1638). Tradescant produced a list in 1634 of

the plants and trees collected by him and planted at ‘The

Ark’ at Lambeth, Surrey. In 1610/11 he was sent by Robert

Cecil to the Low Countries to collect fruit trees, though the

English names in his lists were probably collected earlier.

Tradescant died in 1638 at the age of 68, so the 1634 date of

this apple list was at the end of his life and the various fruit

trees probably existed much earlier. The document, with others,

passed to Tradescant the Younger (who did his collecting in

the Americas) and then to Elias Ashmole, finally residing in

the Bodleian Library at Oxford. Tradescant the Elder included

both 'Smelling Costard' (the only reference) and Grey Costard.

John Tradescant the Elder and John Parkinson (below) were friends

and great mutual admirers.

Returning to

the timeline of references, William Lawson in ‘A New Orchard

and Garden’, of 1597-1618, said “Of

your apple-trees you shall find a difference in the growth.

A good pippin will grow large, and a Costard Tree: stead them

on the North side of your other apples...” The

first description (albeit brief) came in 1629 when John Parkinson

published his ‘Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris’

and wrote of two different Costards! "The gray Costerd is a good great apple, somewhat

whitish on the outside, and abideth the winter’ and ‘The

greene Costerd is like the other, but greener on the outside

continually". We now have something to pursue. It

is a large apple, a vigorous tree, of quality and lasting over

the winter, but with different colours. The ‘greene Costerd’

is quite possibly the Green Custard which is still known and

is a large, green, ribbed apple, which will keep over the winter.

In 1676 the Philosohical Transactions of the Royal Society include

"All sorts of English Apples, as Pearmains, Pippins,

Russetens, Costards". In 1716, Stevenson, in 'The Young Gard'ner's Director'

wrote "The

names of the best sorts off Apples...Costards, Lordings, Pearmains,

etc.". This reinforces

the implication that the Costard is a type of apple, perhaps

in the ilk of Pippins and Pearmains, rather than a single variety,

and Lawson has told us his Costard is a tall growing tree.

|

Green Custard

|

At

this point we have to address the confusion between Costard and

Catshead, which seems to have arisen early in the 19th century.

Comments upon this will punctuate our narrative, but for the moment

we only observe that Parkinson described both Catshead and Costard,

separately. From 1669 onwards, through various editions of the

‘Pomona’ attached to his ‘Sylva’, John

Evelyn wrote of both Catshead and Costard separately. In 1670,

Leonard Meager in The Compleat English Gardner’ listed three

types of Costard, ‘the White, Grey and Red’. John

Rea in his ‘Flora seu de Florum Cultura 2nd edition’

of 1676 repeats white, gray and red. John Worlidge in his ‘Vinetum

Britannicum’ of 1678 said that he had not seen it but that

‘it was in many places of esteem’. He also noted Catshead

separately, as did John Ray in his ‘Historia Plantarum Generalis’

of 1686 who wrote of the Costard-Apple, as well as ‘go-no-further

or Catshead’. Ray, who wrote in Latin, said of the Costard

“Nor should be omitted from this

catalogue that which is called 'The Costard Apple', that was once

held in such high esteem, that an apple seller, as a kind of epithet,

was known by this name. For they are still today called 'Costard-mongers'”.

We are very grateful to Bryan

Ward-Perkins and Mark Norman for their help with a difficult Latin

translation, beyond our skills.

|

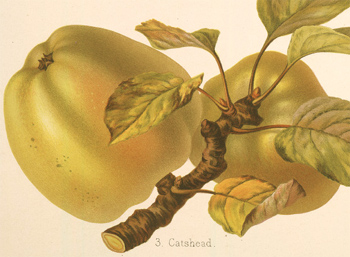

Catshead

|

|

Catshead

Catshead, Courtesy of Sheila Leitch, Marcher

Apple Network, from the Herefordshire Pomona

|

|

John

Mortimer in ‘The Whole Art of Husbandry’ in 1708,

repeated Worlidge’s words but added that it was ripe in

October. He also wrote of Catshead. Richard Bradley, in his Dictionarium

Botanicum of 1728 gives a list of apples "as are accounted the best for Eating and Baking

from Mr. Whitmill’s catalogue, Gardiner and Nursery Man

at Hoxton". He includes Costard Apple as well as Catshead.

If the Costard began its history

as a Class or Type of apple, it now seems to have become a 'Variety'.

We must also bear in mind that apples have a strong tendency to

mutate and shift their nature and appearance over time. If a shoot

on a tree has mutated and that shoot is used to graft another

tree, the fruit from the new tree might not look or taste quite

the same as that from its parent. Please bear this in mind as

we move onto the next point in history and a very significant

one. The old Costards might now have quite different natures and

appearances. We must also factor in the 'Little Ice Age' that

followed the 'Mediaeval Warm Period'. From 1650, ice and glaciers

expanded into the North Atlantic, affecting climate across northern

Europe, with significantly lower temperatures. This period did

not go into reverse until 1850, so all the early and middle period

writers were commenting upon ripening times and storing periods

that would not be observed after 1850 and particularly would not

be seen under global warming. Costards might be ripe in late September

or early October and might not store so well over the winter.

One of the truly great and one

of the very few authoritative writers on gardening of his age

was The Reverend William Hanbury of Church-Langton, Leicestershire.

His ‘A Complete Body of Planting and Gardening...’

in 1770, was written from real experience, rather than from repeating

the already repeated words of others. He set up plant nurseries

in his area and used the proceeds exclusively for improvements

locally - notably the Church and a new school. His descriptions

of apples could not have been written without great familiarity

with them. His varieties hark back to names known in the 17th

century or early 18th, rather than new names that were becoming

known late in the 18th century. As you might have guessed, he

included the Costard! It “Is a large, irregular Apple, finely striped with red, especially

on the sunny side. The flesh is tender and juicy, but not very

agreeable to the palate. This Apple is in universal request for

baking, and affords the best sauce yet known for a goose, roast

pork, and the like savoury meats.” This is the first

reference to a striped apple - perhaps now mutated. The description

takes us further.

Richard Weston, in ‘The

Gardener’s and Planter’s Calendar’ of 1773,

said the Costard was ripe in December. In 1778, Thomas Mawe and

John Abercrombie, in ‘The Universal Gardener and Botanist’,

said of the Costard Apple "large,

irregular and red striped" and just two lines lower

said "Cat’s-head Apple, very

large, for culinary uses".

We know a little

more. ‘A’ Costard is ripe between October and December,

and will last longer, is large, irregular and red striped. Both

Costard and Catshead were included in ‘A Brief Catalogue

of Fruit Trees, sold by William Pinkerton, Nursery and Seedsman,

in Wigan, Lancashire, 1782’. The list included 121 varieties

of apple. In 1786 the 'Gentleman's Magazine' recorded "Upon the Costard I grafted the Broadin or Garden Apple".

William Forsyth in ‘A Treatise on the Culture and Management

of Fruit Trees’ in editions up to 1810 listed Costard and

Catshead. The Costard still appeared to exist and be known into

the 19th century, but then a pomological disaster struck.

In the first

collection catalogue of the London Horticultural Society of 1826

no Costard was listed but there were two Catsheads – ‘Catshead’

and ‘Round Catshead’. The latter was given a synonym

of Téte du Chat (of Jersey). This was also the case in the 1831 edition, but the 1842 edition

now listed Costard saying ‘see Catshead’ and Costard

(and Coustard) were given as synonyms of Catshead, under that

entry. It still included Round Catshead separately. Catshead was

described as being pale green, oblong, large, for kitchen use,

top quality and ripe from October to January. Round Catshead was

described as yellow, roundish, large, for kitchen use and ripe

from December to March. The timing of this allocation coincides

with the entry under Catshead by George Lindley, in ‘A Guide

to The Orchard and Fruit Garden’ in 1831. Lindley was the most influential authority and writer

of the time. Though otherwise meticulous in his research and precision,

he made a terrible mistake. He said that Catshead was the same

as the Costard of Ray (1688) and for no reason that can be fathomed.

Ray had noted both separately as did so many other earlier writers.

The ‘synonym-isation’ of Costard led to ‘no

further enquiry’ and to its decline, as well as to an increasing

plurality of various Catsheads, under the confusion.

|

In

the 1843 catalogue of John and Charles Lee, nurserymen of Hammersmith,

London, There was a reversal of names in that they listed

Catshead (in use from October to January) and Catshead Round

(in use from December to March) and they gave Costard as a synonym

of Catshead Round, not to Catshead. This nursery, as 'Lee and

Kennedy', had been going since the first half of the 18th century

and would have been familiar with Catsheads and Costards. Perhaps

they chose to correct the London Horticultural Society. Either

way, the nursery trades were now selling two types of Catshead

and no Costards under that name. Perhaps old Costard trees can

still be found in London, though the nurseries of Lee and Son, have long

gone, to houses and offices.

The

next observations on the Costard came with the publication

of ‘British Pomology’ by Dr Robert Hogg, in 1851.

He was manifestly describing apples from sight, as the references

he gave for the entry under Costard gave no detail on the

apple for him to repeat. Whether it was the right apple is

less than clear, as subsequent descriptions by him were different.

The entry in British Pomology reads “Above medium size, two inches and three quarters,

or three inches wide, and three inches and a quarter high;

oblong, but narrowing a little towards the eye, distinctly

five-sided, having five prominent ribs on the sides, which

extend into the basin of the eye, and form ridges round the

crown. Skin, smooth, dull yellowish green, strewed all over

with embedded grey specks. Eye, partially closed with long

acuminate segments, and set in a rather deep and angular basin.

Stalk, about a quarter of an inch long, inserted in a round,

rather shallow, and narrow cavity. Flesh, greenish-white,

tender, juicy, and with a brisk, and pleasant sub-acid flavour.

An excellent culinary apple of first-rate quality. It is in

season from October to Christmas. The tree is hardy, a strong

and vigorous grower, with strong downy shoots, and an abundant

bearer.” He adds that “The

true Costard is now rarely to be met with.” While

Hogg says the Costard will go to Christmas, Parkinson had

said that it “abideth the winter.”

In 1872, the

famed nurseryman of Merriott, in Somerset, John Scott, published his ‘The Orchardist’

and though, frustratingly, he failed to give a full description

of the Costard, he had some interesting observations to make

– and, clearly, from personal knowledge. He described

Costard as being large, of top quality, for the kitchen and

lasting till April. “Long and somewhat square, or 5-angled or ribbed,

from which it has evidently deserved its Latinised name, i.e.,

Costa, a rib; one of our oldest English Apples and is one of

our best kitchen fruit. Tree very hardy, and a great bearer;

it is of low spreading growth, and produces its fruit abundantly

as far north as Breadalbane in Scotland, where I have seen it

bear heavy crops; it there bears the name of Catshead, as it

does in many other places, although wrongly.” He

also describes the Catshead, in detail, separately, while noting

the confusion that exists between Costard and Catshead. He says

of Hogg’s description of Catshead “there

appears to me to be a little confusion in the description which

Dr Hogg has given of this fruit in his pomology. The description

seems to belong to two different sorts of apple, viz., the Costard

and Catshead. The first is always, here, oblong and five-sided,

but the second always of an irregular roundish form, and is

grown plentifully in this neighbourhood, as is also the Costard.

The Doctor says—‘Fruit large, three and a quarter

inches broad and same in height; oblong.’ This cannot

be ‘the Cat’s Head’s weighty orb’ but

would do for the Costard. The two fruits are often confounded

by writers, yet are very distinct.” Scott’s

description of Catshead was of a large apple of top quality “as a cooking Apple, November to February. Fruit

very large, round and irregular in outline; skin smooth and

unctuous, fine pale green, which becomes very light greenish

yellow at maturity, with a brownish tinge on the sunny side,

strewn with minute dots; Stalk short, inserted in a shallow

irregular angled cavity; eye large and open, set in an irregular

angled deep basin; flesh tender and sweet; juice plentiful,

pleasantly acid, and perfumed. A very old and useful Apple for

dumplings.” (Though much

of this was borrowed from Hogg).

|

The

Costard still existed as late as 1887 when the Cheshire Observer

said "Messrs James Dickson and Sons have an unsurpassed

collection of Apples: Waltham Abbey Seedling, Costard Apple,

Reinette du Canada."

After

this point, the quest becomes very murky. Perversely, the descriptions

are fuller and they have been taken in modern times as the yardsticks

against which to identify the Costard, but the evidence is flawed.

We must address the accounts of the ‘Herefordshire Pomona’

and the fifth edition of ‘The Fruit Manual’. The

former was written between 1876 and 1885, by Dr Hogg and Dr

Bull, and the latter was published in 1884 and written only

by Dr Hogg. There does not appear to be any record to confirm

which of Hogg’s writings were completed first. The stark

revelation is that the descriptions in these major works are

inconsistent with each other and also inconsistent with Hogg’s

‘British Pomology’, 1851.

|

|

The

1884 ‘Fruit Manual’, under Costard, starts

describing the features of Catshead, saying the Costard

is “no doubt synonymous

with the Catshead and this accounts for George Lindley

saying they are the same variety.” He then

qualifies the situation and in the same description he

says “Modern authors make

the Costard synonymous with the Catshead, chiefly, I think,

on the authority of Mr George Lindley, who has it so in

the ‘Guide to the Orchard’; but this is evidently

an error. All the early authors who mention both varieties

regard them as distinct.” He points out that

there are two other varieties of Costard which “are

undoubtedly distinct” namely the Herefordshire Costard

and the Gloucestershire Costard. He describes them separately.

Neither is quite the description he offers of Costard

in British Pomology of 1851. Of Herefordshire Costard

he says “Fruit, large,

three inches and a half wide at the base, and four inches

high; conical, larger on one side of the axis than the

other; towards the apex there is a waist, from which it

narrows abruptly to the eye, where it is much ridged;

it has prominent ribs and an undulating outline. Skin,

fine deep yellow on the shaded side, and bright red on

the side exposed to the sun, where it is streaked with

red and orange. Eye, small, set in a deep narrow basin,

with erect convergent segments, half open. Stamens, median;

tube, long, funnel-shaped. Stalk, about half an inch long,

stout, inserted in a very deep and prominently ribbed

cavity, sometimes with a swelling on one side of it, which

presses it in an oblique direction. Flesh, white, very

tender, with a mild sub-acid flavour. Cells, long and

narrow, pointed, ovate; axile, open. A very handsome apple,

much esteemed for roasting, and especially for baking;

in use from November till January.” He received

this apple from Dr Henry Bull, the original tree not being

a large one (at about 50 years old in 1884) and having

generally been a shy bearer. Of Gloucestershire Costard

he says “Fruit, very large, three inches wide, and three

inches and a half high; conical or somewhat cylindrical,

prominently ribbed, and with ridges round the eye; it

is longer conical than the Herefordshire Costard. Skin,

almost entirely covered with crimson streaks, mottled

with the yellow ground colour which shows between the

streaks; on the side which is shaded there is less crimson,

but more of the rich deep yellow; the surface is strewed

with minute dots. Eye, closed, with long segments, set

in a narrow, pretty deep, and plaited basin. Stamens,

basal; Tube, conical. Stalk, half an inch long, stout

and deeply set in an irregular furrowed basin. Flesh,

yellow, tender, sweet, and of good flavour. Cells, large,

open, but not wide open like the Codlins, as might be

expected from the appearance of the fruit; elliptical;

axile. This is a very handsome apple, of good flavour;

but more adapted for cooking than the dessert. It keeps

well till January.” He was describing a particular

fruit, received via Dr. Henry Bull. |

|

Gloucestershire and Herefordshire Costards,

Courtesy of Sheila Leitch, Marcher Apple Network,

from the Herefordshire Pomona |

The

bombshell is that these descriptions were allocated

to different names in the Herefordshire Pomona, such

that the Herefordshire Costard in the Herefordshire

Pomona carried the description of the Gloucestershire

Costard in the Fruit Manual and Vice Versa. The descriptions

were not identical but enough phrases were repeated

to be confident that some significant error occurred

between the publications of the two works. The Herefordshire

Pomona included coloured plates of the two apples, which

seem consistent with the text attached, but the error

makes both publications untrustworthy. The Herefordshire

Pomona also misquotes Parkinson (1629) saying that the

Costard ‘abideth not

the winter’, whereas Parkinson said it

‘abideth the winter’.

Hogg’s Fruit Manual did not make this mistake

and quoted correctly.

We

have two descriptions that cannot be attached with any

confidence to two names, besides which, neither appears

to accord well with the brief descriptions of the Costards

that were made in centuries before.

|

| The

trail of the Costard was rather cold by 1883, when the Royal

Horticultural Society held its National Apple Congress at

Chiswick. Two different Costards and two different Catsheads

were exhibited and described by Barron, the author of the

report of the Congress. One Costard was exhibited by Cranston

Nursery of Hereford and was described as being very large,

oblong, green, soft, early season and a fine culinary apple.

The other was exhibited by Messrs J. Jefferies and Son of

Cirencester, Gloucestershire, being described as small,

culinary, conical, tapering, angular, yellow, streaked,

acid, mid-season and of third quality. By virtue of season

or size, neither could be the true Costard. After the subsequent

RHS exhibition of 1888, the report included an appraisal

of apples suited to growing in Lincolnshire, as selected by Mr Johnson, Mr Picker and Rowson

Bros. Nursery. Both Catshead and Costard were included,

so perhaps Lincolnshire might still have the Costard growing, if anonymously. |

|

The

20th century held no reliable sightings. Taylor, in ‘The Apples Of England’, 1946,

said that by the end of the 17th century it was fast disappearing

(though there is no evidence to suggest it was disappearing

so early). He added that “the

apples exhibited at shows as Costard are usually other

old varieties.” This statement allows that

not all were other varieties. It is hard to know how he

could be certain that a true Costard was not among them.

He had “not been able to find in England a tree of the Costard” and surmised that “This

historic apple seems to have disappeared.”

Nurseries still offered Costards but Taylor was probably right and that they were other old

varieties. Towards the end of the century and into the

21st the hunt resumed and over-enthusiastic ‘identifiers’

discovered and named several ‘costards’ to

add to the multitude coming out of the 19th century. We

now have, apart from several apples simply named Costard,

the following names - Cornish Costard, Crimson Costard,

Coustard, Custard, Custard Apple, Custard Scarlet, Downway

Costard, French Custard, Gloucestershire Costard, Green

Custard, Greene Costerd, Gray Costerd, Herefordshire Costard,

Martin’s Custard, Pope’s Scarlet Costard,

Red Costard, Red Custard, Royal Costard, Scarlet Costard,

Summer Costard, White Costard, White Custard, White-Costard

Gray, Wotton Costard and more added yearly. We might also

add in apples called ‘costing’ or ‘costin’,

such as Summer Costing and White Costin, which might be

corruptions of Costard. Most of these are not now known,

their names not being attached to living examples.

If

we take the view (as we do) that apple trees can live

much longer than commonly supposed and that, in times

past, local owners would have grafted new trees for their

own use, to replace their ancient ones, and would have

passed grafts around, then true Costards are probably

still growing as old anonymous trees, of which there is

a very considerable number. The concern, in the modern

age, is that they are often carelessly and incorrectly

awarded the wrong name. The ongoing confusion with Catshead,

started by Lindley (1831) and noted by Hogg and Scott,

has now resulted in a disastrous number of different apples

being identified as Catshead, purely on the basis of being

large, green and ribbed. Some might be Costards. We have

observed, over the years, that some apples which are not

Catshead have been exhibited as such. They are large,

green, ribbed, oblong, often with a waist, late season

and keeping over the winter. The apple we have named as

Wotton Costard is strikingly similar to several sightings

of these non-Catsheads, almost all encountered in the

western counties. Given Scott’s observations on

this regular misnaming, considered above, we wonder if

they might just be the true Costard. It is only a ‘might’. |

|

Costard (Howlett)

Pope's Scarlet Costard

|

| What

do we really know of the Costard? Not enough!

1. If, in the 13th century

it was a single variety, then it became two, early in

the 17th century and then three, later that century. It

might have been a class of apple, like the Pippin or the

Pearmain.

2. If we assume that

the old Greene Costerd still exists as the extant Green

Custard then we have a shape, form and character to go

on.

3. If we believe that

really old varieties still exist as living old trees,

replicated over the centuries, we can have faith that

the old Costards still exist, albeit without their names.

4. If we take Scott at

his word, we know that Costards are not as big or rounded

as Catsheads and are green, oblong, five sided and late

season keeping apples.

5. If we allow the hypothesis

that Costards are a ‘type’ of apple we might

still find the Herefordshire and Gloucestershire Costards,

noted by Hogg and Bull, which are still close enough in

time for trees to exist. Unfortunately, the confusion

with their descriptions will make it difficult.

|

Of the various apples

purporting to be Costards, most can be dismissed. There

is a Herefordshire Costard, known and grown in places

in Herefordshire, which is a green-yellow ribbed apple

and not the red coloured one of Hogg. The Costard Apple

of Hereford which is held at Wisley might be the same.

Hatfield House have two Costard trees that were planted

in the 1970s from trees supplied by the original Keepers

Nursery (the apple being different from the Costard

being supplied by the current Keepers Nursery). The

Hatfield Costard appeared very close to the coloured

Herefordshire (or Gloucestershire) Costard of Hogg,

but a recent DNA test showed it to be the same as Pope’s

Scarlet Costard – an apple bred in the early 20th

century. The appearance seemed very different between

the two, but it just goes to show how deceptive apples

can be. It seems probable that Pope’s Scarlet

Costard has turned up in several places as just ‘Costard’.

The Costard now sold by Keepers Nursery shows a green

apple and is probably Catshead. The old Keepers Nursery

supplied Cressing Temple Barns (Essex) with a Green

Costard and a Red Costard about 25 years ago and Rebecca

Ashbey, the horticulturist there, provided us with scions

to graft here. A recent DNA profile test showed that

the Green Costard was Catshead and the Red Costard was

Pope's Scarlet Costard. We also have the Costard form

Berrington Hall, Herefordshire, and that turned out

to be the same as Scotch Bridget, after profiling. There

is also a Crimson Costard known to the Marcher Apple

Network in Herefordshire, though we have not seen it,

or know of the provenance of its naming. We also have

to consider a set of apples, very similar, if not the

same, named Catshead in the western counties but which

are wrongly named. The ancient Wotton Costard is also

very similar in appearance to these. It is hard to have

faith in other contenders, read on! All those brought

into the National Collection at Brogdale, under the

name Costard, have been found to be wrong. Their Costard

(Supposed) and Costard (Howlett) are both Pope’s

Scarlet Costard. However, we now have two more candidates,

(possibly three) that have emerged since we first wrote

this appraisal. We consider these at the end.

We wrote before - "In

conclusion, frustrating as it is, and dispiriting not

to be able to find such an ancient apple, we must accept

that re-connecting the name to some old tree (which

will still exist) cannot be done with certainty. It

has been our compelling experience that the more an

apple is described, the greater are the inconsistencies

and the greater the confusion. We just don’t have

enough reliable information to go on. Perhaps there

will be some old document, buried in some archive, that

will unlock the mystery. For those of us who savour

mystery and who place 'The Quest' above its resolution,

there will be a perverse hope that the Costard will

never be found. To look at an apple from some ancient

tree and say ‘I wonder if….’ is the

greater pleasure. Regardless, the quest will go on."

We previously updated

this account in January 2021, with some important additions

and we again thank Dr Theresa Tyers, of Loughborough

and at Swansea University, for notifying us of many early references to

the apple, drawing upon her expertise in mediaeval medicines

and their social history as well as her knowledge of

early literature. Her input greatly augmented the narrative

in that update. Now, in November 2022, we have made

further amendments and can finish with some thoughts

on two recently researched apples that have shown on

our radar and have some claim to be missing Costards.

They are different apples, each unmatched in their dna

with other known apples.

|

|

Hatfield Costard

Wotton Costard

Red Costard |

|

|

Herefordshire Costard (Wisley) |

Costard

(Berrington Hall) |

|

The

Lightning Tree/Suzie's Costard

Dr

Suzie Imber is a planetary astrophysicist at Leicester

University, a good friend (as are her parents) and a

human dynamo. While living at East Langton, Leicestershire,

she bought a very old orchard nearby, to ensure its

future as an orchard and for the pleasure of tending

it. For those readers who have been paying attention,

it will not be lost on them that we earlier talked about

the Rev. William Hanbury at Church Langton. There is

also a West Langton. The name Langton comes from Old

English - Lang, meaning Long, and Tun or Ton, meaning

a farm settlement. The area is of great antiquity. Suzie

and her parents called on us to ask what we could tell

them about the variety of apples they brought, a few

years back. We then spent a fascinating day visiting

Suzie, the area and calling in on her friend Mark Newton,

who now owns Hanbury's rectory at Church Langton, and

is man of great local knowledge. The Rev. William Hanbury,

as we detailed above, set up several plant and fruit

tree nurseries around the Langtons in the mid 18th century.

Suzie's very old trees were likely to have come from

the Hanbury pool. Could one be a Costard, as described

by Hanbury? One, called the Lightning Tree could fit

the bill. Before a lightning strike the tree was around

50ft tall, but is now around 35ft. It is of spreading

habit, as in Scott's description, but hardly low, as

he says. Perhaps he was looking at younger trees. William

Lawson in ‘A New Orchard and Garden’, of

1597-1618, said “Of your

apple-trees you shall find a difference in the growth.

A good pippin will grow large, and a Costard Tree:..."

|

|

The

Lightning Tree/Suzie's Costard |

The Lightning Tree/Suzie's Costard |

The Lightning Tree/Suzie's Costard

|

This is a

truly old tree and its DNA has not been matched with

any other tested tree. Other trees in the orchard have

found matches but not of middle aged or newer varieties.

The whole orchard is old. But what of the apples, shown

below? Hanbury's description of the Costard, repeated

here to save you time finding it above, said it “Is a large, irregular Apple, finely striped with red, especially

on the sunny side. The flesh is tender and juicy, but

not very agreeable to the palate. This Apple is in universal

request for baking, and affords the best sauce yet known

for a goose, roast pork, and the like savoury meats.”

That description fits this apple prefectly (though caution

says it could fit others). We would say that the apple

is pleasant enough to eat raw, when fully ripe, but

otherwise the fit is complete. From fruit received in

mid November 2021 (a more reliable year than fruit from

the hot and dry year of 2022) our notes were thus. The

flesh is cream to pale green, green along the core line.

It slowly discolours when cut, but not so much as some.

The apple is fairly weighty and the flesh is not over

juicy, of an open texture, firm rather than crisp. Pleasantly

sweet and with a fair flavour, a little of lemon. Fine

to eat but not the best. Cooked, it softens very quickly

and goes to a mashable puree consistency. The flavour

is very much enhanced and it has all the right elements,

perfectly balanced. The flavour is quite complex, and

very good indeed. Very rich and no need for added sugar.

The flesh has gone yellow after cooking. At the end

of January 2022 we noted that the apple was still solid

but the flesh inside had now gone a little tough. The

flesh was firm, not soft and moist enough. The flavour

was good, not sharp and was a reasonable eater. It cooked

fairly quickly and broke down. The flavour was pretty

good but maybe not as good as before in the autumn.

Sweet enough without sugar and rich enough but maybe

the quality had faded a bit. In any one year, especially

in warmer years, it is enough that this apple lasted

to the end of January.

This apple

- Suzie's Costard - has a legitimate

claim to be the Costard of Hanbury or the ancient Costard

if these are the same! It might be the Costard of Parkinson,

if that had undergone some mutation to introduce stripes,

but the Gray and the Greene Costards of Parkinson might

have other claimants.

Apples Late September 2022

|

Apples

Mid-October 2022 Apples

Mid-October 2022

Apple November 2021

Apples Mid November 2021 |

The

Sawmill Costard(s)

As

we noted much earlier in this article, the Costard existed

with Sir Thomas Tresham at

Lyveden New Bield in Northamptonshire in the

late 16th century. His wife, Dame Muriel, after his

death, donated Costards to Robert Cecil at Hatfield

House in Hertfordshire in 1609. John Tradescant the

Elder, a friend and collaborator of Robert Cecil, was

also familiar with the Costard. Peter Oakenfull, Ecologist

and 'Apple Hunter' - a friend of ours - had a personal

communication from a former head gardener to The Dowager

Lady Salisbury that this and other trees supplied by

Lady Tresham, were planted in the walled Vineyard at

Hatfield. Though some ageing apple trees are still in

the Vineyard garden, no truly ancient apple trees still

exist in this very large walled garden and none that

could be considered Costards.

In

an orchard at the Old Sawmill at Hatfield there are

two apples which could fit the 'Costard' brief. Peter

says 'the Vineyard is around 200m from Sawmill but there

were other orchards towards Sawmill... generically they

would have most likely been considered as being in the

Vineyard area though'.

Could they have come from a decrepit Tresham tree in

the Vineyard, making their was from sequential graftings,

to the Sawmill? There are two trees there which bear

large, ribbed, green apples, late in season and lasting

into the New Year. Both are cooking apples that can

be eaten raw at full maturity in November. One is very

old and the other was seemingly planted in the first

part of the 20th century, though accurate estimates

of apple tree age are very difficult to make. Apple

trees are full of surprises. It might be that this younger

tree was grafted from a much older tree that was failing

in the same orchard. Being young does not signify that

the variety is young. Both trees have DNA unmatched

with all others that have been tested and each is different

to the other as regards DNA.

We

call them 'Sawmill Old Costard' and 'Sawmill Young Costard'

for the time being, though Peter has favoured

'The Hatfield Costard' for the older one.

|

Sawmill Old Costard Mid October 2022

Sawmill Old Costard November 2020 |

Sawmill Young Costard October 2020

Sawmill Young Costard Mid October 2022 |

|

|

|

|

A Visitor

to the Old Costard, before damage and pruning.

|

|

This orchard

was rather overgrown in 2020, with many parts in deep

shade, so it was not easy to make definitive judgements

on the quality of the fruit at that time, but both apples

were pleasant to eat and cooked well, breaking up, and

became very rich. Over the winter of 2020/21 the Hatfield

Estate pruned some boundary ashes and a Lawson Cypress,

which caused the loss of a major bough of the Old Costard,

but the tree is safe and continues to fruit. Peter has

provided apple samples and contributed greatly to the

painstaking extraction of the facts around the case.He

is waiting (as at early November) to gather further

samples from both trees at the peak of ripeness and

to observe the keeping qualities into the new year.

Our thanks go to him for his energy, enthusiasm and

efforts in all things pomological.

There is

more to be written, but as we stand we have some possibilities

of rediscovery of old Costards, albeit we are still

inclined to believe that Costards were a class of apples

rather than single varieties. There is another contender

that we have not yet discussed. This is another apple

very close to The Rev. William Hanbury's patch, but

that is for another day. Other distinct, green, ribbed,

large, dual purpose apples, ripe late in the year and

storing, are out there. We might still never know the

true Costard(s) but the search has its own rewards -

in discovering ever more truly interesting and long

forgotten varieties.

Updated 2/11/2022

|

|

|

|

|

|